I consider privacy as important but I am not a government-conspiracy nut. Even so, the passed Investigatory powers bill is extreme, and it should worry you. Political avenues have been exhausted. Legal challenges are unlikely to succeed unless lawyers can argue that the IPB is incompatible with fundamental human rights.

The only option left is technology.

First, some motivation by showing examples of what will be stored. Here is the government’s clarification of Internet Connection Records. Also read Privacy International’s interpretation which is less charitable.

A normal day could look like this:

- 1:00 am. Phone automatically downloads mail from Fastmail.

- 1:13 am. Phone reconnects to whatsapp.

- …

- 7:00 am. You check Twitter and Facebook.

- 7:01 am. Your Philips Hue connects to the Internet.

- 7:02 am. You check the weather.

- 7:10 am. You turn on Radio 4 on iPlayer.

- …

- 8:00 am. Phone reconnects to Facebook messenger.

- 8:10 am. You looks at some mildly erotic pictures on tumblr (subdomains are enough).

- 8:19 am. You shop at topshop.

- 8:46 am. You visits Amazon to check for a Christmas present.

- 9:00 am. Phone synchronises with Google docs.

- 9:22 am. You check Google docs on their work domain.

- 9:25 am. You check LinkedIn because your current job isn’t the best.

- 10:13 am. You check a political blog post you found on Twitter.

- 10:13 am. Click external link to other political blog post.

- 10:14 am. Click on link to right-wing activist page.

- …

So by 10:14 am I know that you use Fastmail, Facebook, Twitter, whatsapp, Google docs, LinkedIn, shop at topshop and Amazon, what kind of political blog you read, what links you are interested in (you clicked them after all), that you like mild erotica (you spent 9 minutes clicking around), and that you also own a Philips Hue.

Now extrapolate this to a year. Everything you are interested in, or were interested in for 5 minutes, every thoughtless click, every service you use, when you use them, how often you use them, when you are on holiday, where you are going for holiday, which airline you used. All that can be easily deduced from your internet connection records.

It falls to the ISPs to record this data, and the ISPs have to soak up some of the cost. They’re not incentivised to splurge on data safety. At the same time this data is very interesting for a large number of malicious actors (state and non-state). In addition, history shows that the “tightly regulated” access will not be so.

To summarise: This is bad news.

Setting up an OpenVPN server

I run my VPN on EC2. My NixOps config looks like this.

In my config you can see that we need four files for OpenVPN:

ca /run/keys/ca.crt

cert /run/keys/server.crt

key /run/keys/server.key

dh /run/keys/dh2048.pem

I’m using a bunch of shell-scripts called easy-rsa to create those four files. The set of files is called a self-signed authority. “self-signed” because you trust yourself here.

On Debian a typical flow looks like this:

$ make-cadir test-ca

$ cd test-ca

$ emacs vars

# .. edit vars, specifically change the KEY_NAME

$ source vars

$ ./build-ca

# .. fill in details. Just hitting enter for each default should be fine.

$ ./build-dh

# .. will take a while

$ ./build-key-server server

# .. This script will ask "Sign the certificate?" and you reply "y"

# .. Also reply "y" to "commit?".

After this you will find a keys directory with the 4 files required. Use those in your configuration. It’s important files ending in .key stay private - if you lose them, or publish them on GitHub you need to re-create all your keys!

Android

I’m using OpenVPN for Android by Arne Schwabe. It’s GPL and available on GitHub if you prefer to build your own APK.

First we create a key for our phone specifically:

$ cd test-ca

$ ./pkitool phone

Generating a 2048 bit RSA private key

...

$ ls keys/phone.*

keys/phone.crt keys/phone.csr keys/phone.key

You need to somehow get keys/phone.crt, keys/phone.key and keys/ca.crt onto your phone. phone.key is secret and must be treated as such. You could e.g. copy via USB, or with Bluetooth file transfers.

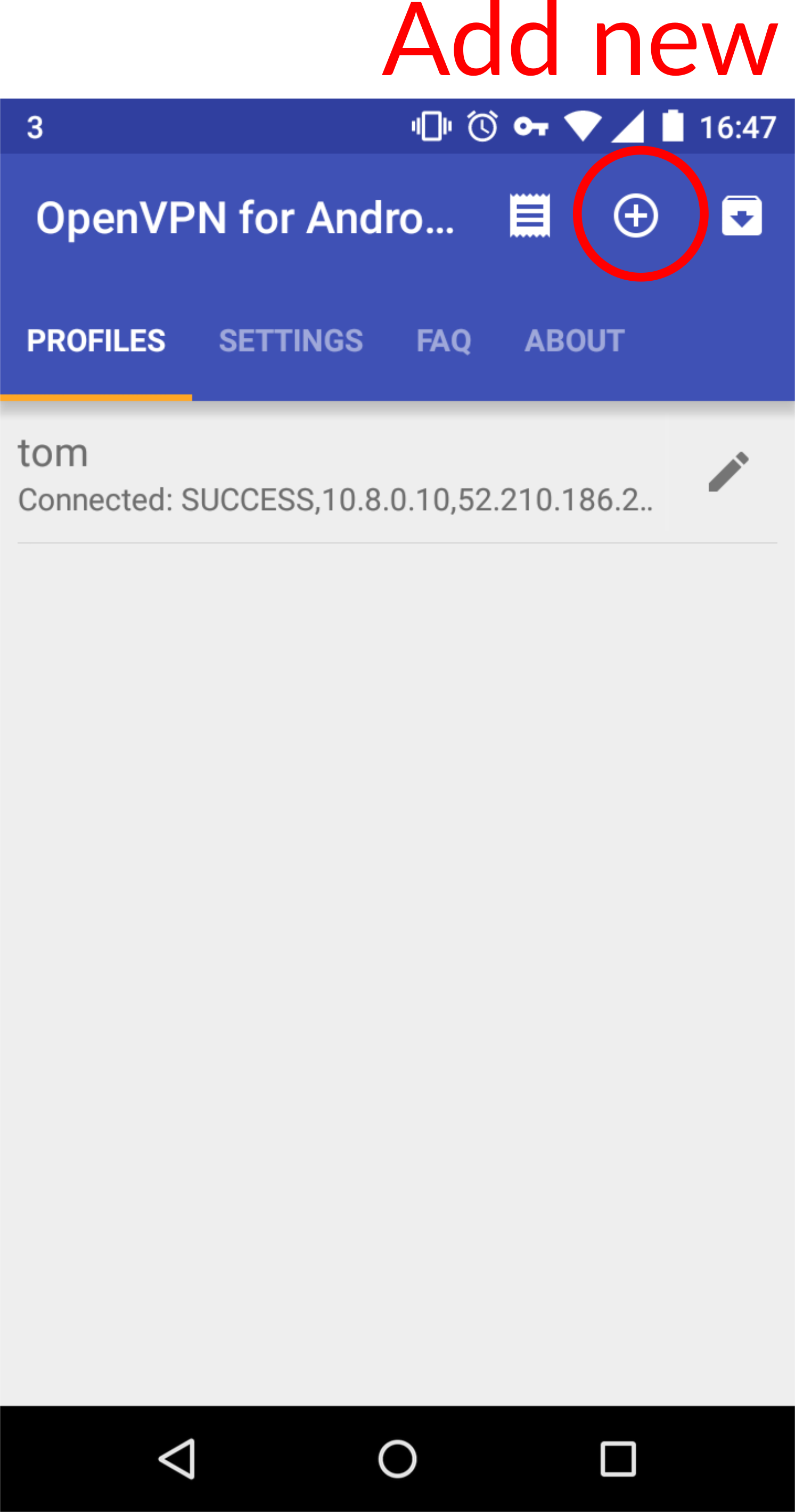

After starting the OpenVPN app you can find a small plus (+) at the top to add a new connection:

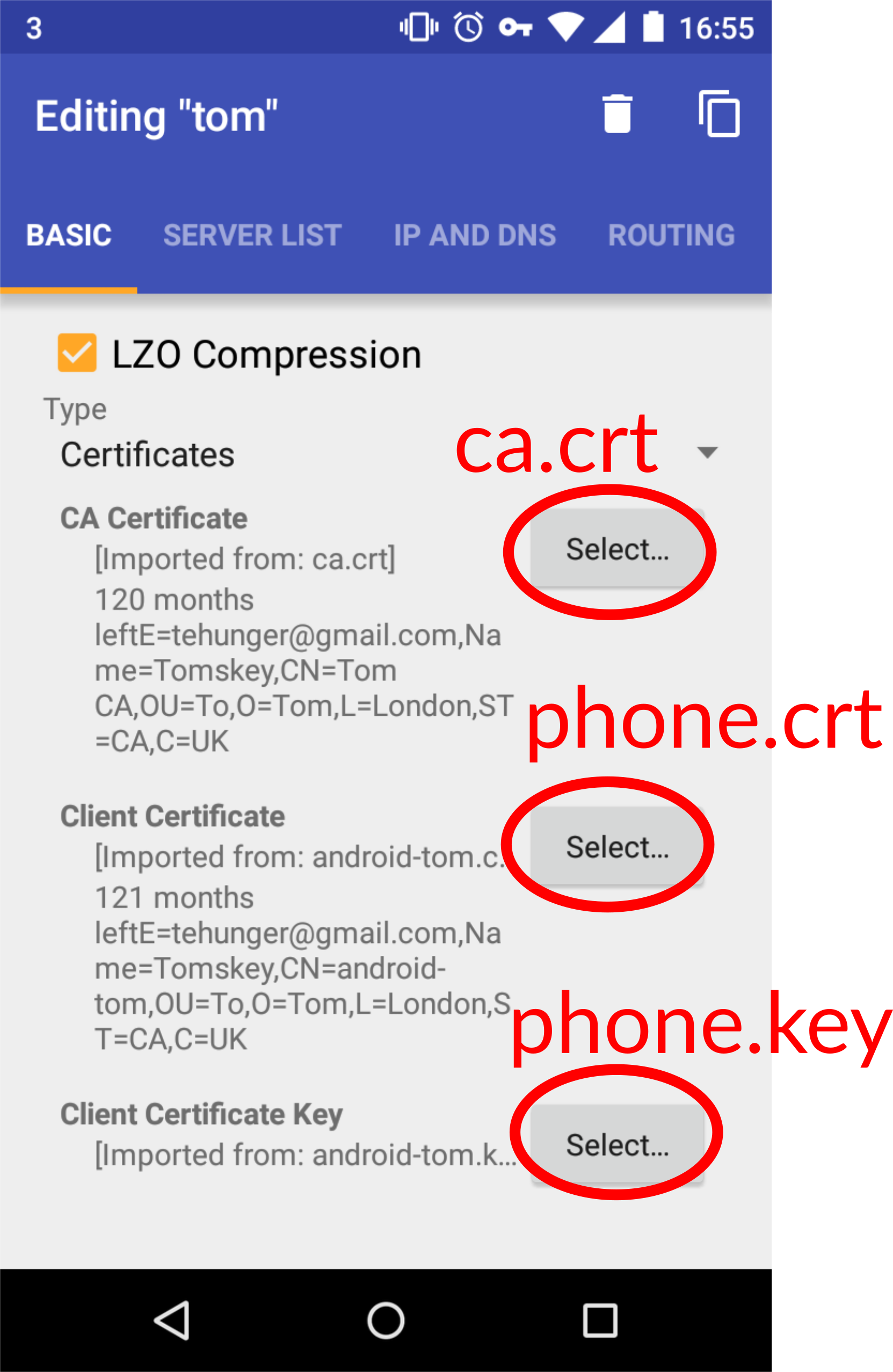

Now you add the three files we just transferred:

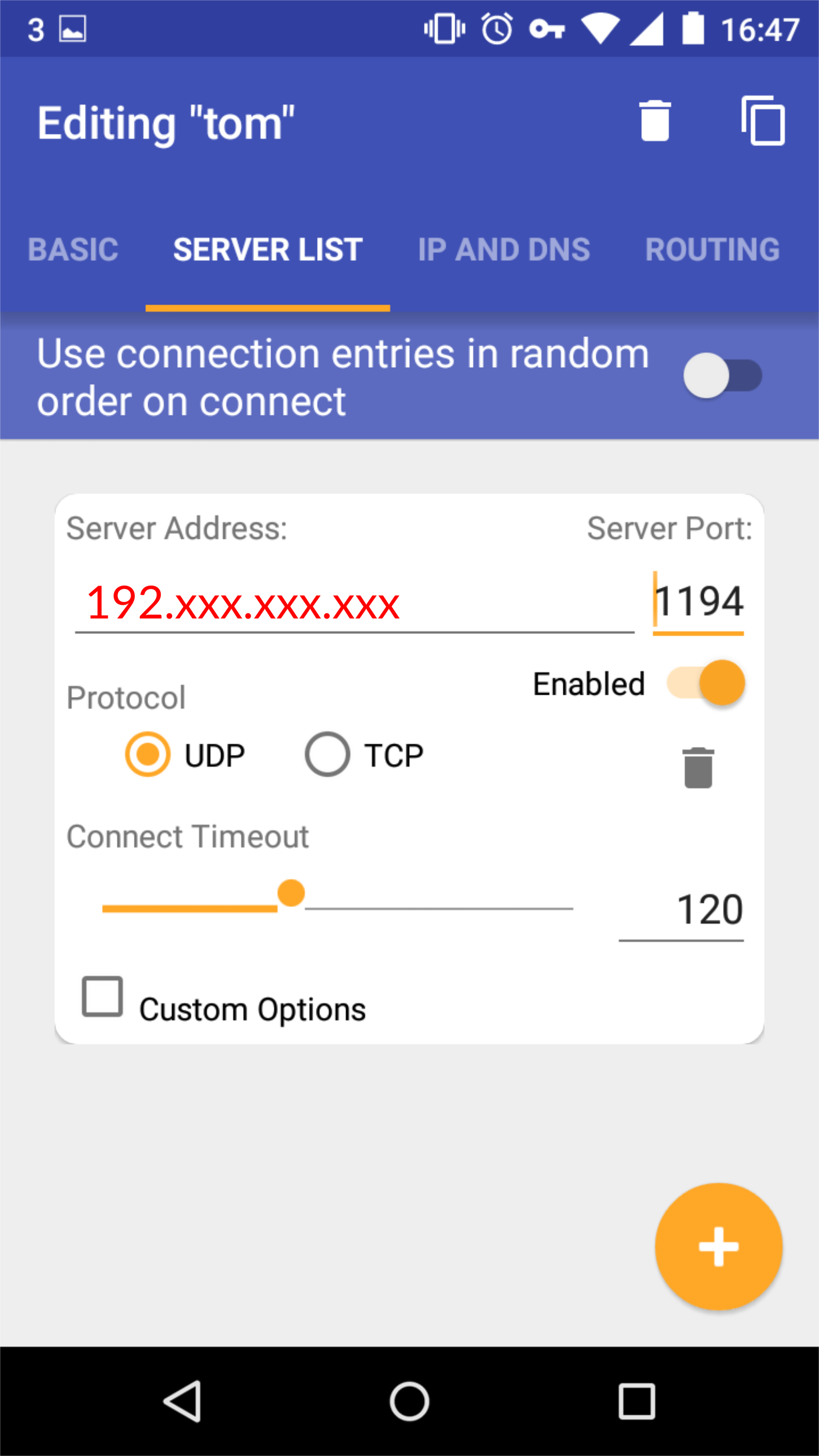

You also need to point the VPN to your VPN server:

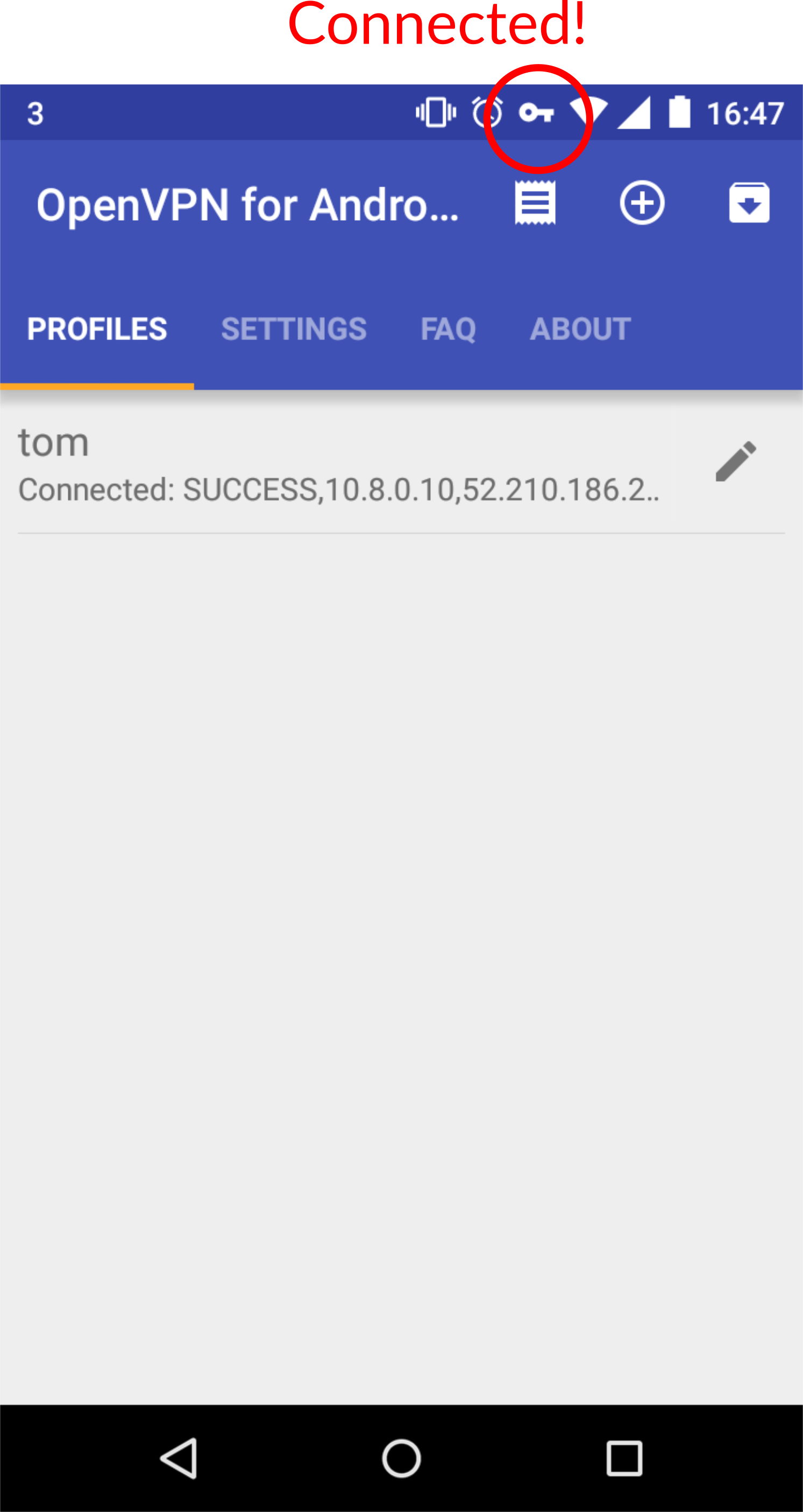

If everything worked you will see a small key at the top:

A lot can go wrong along the way! If anything breaks I recommend googling the specific error messages. A common gotcha is a mismatch between the server key name (KEY_NAME from above) and the server address. If your KEY_NAME is example.org then your server should run under the domain example.org). You can set a custom name under “Authentication / Encryption”.

Other devices

I run Gnome3 with Network Manager but I won’t show detailed screenshots. The steps are similar to Android. First, install the OpenVPN network manager plugin:

sudo apt-get install network-manager-openvpn

Then generate a new key:

$ cd test-ca

$ ./pkitool laptop

Generating a 2048 bit RSA private key

...

$ ls keys/laptop.*

keys/laptop.crt keys/laptop.csr keys/laptop.key

In Network Settings add a new network (+ at bottom left) and fill in the details. Note that sometimes LZO compression isn’t on by default. You can enable it under settings -> advanced.

Notes

- AWS bandwidth costs ~ $0.10 per GB. So don’t binge watch Netflix over your VPN.

- A VPN introduces latency. Your Internet will feel slower.

- Make sure your VPN server is up-to-date.

- You will still leak data in a myrad of ways (clever ad-tech, high-entropy browser fingerprint). But when an ISP leaks connection records you’ll be better off than the other pool souls.

A lot of work …

Sadly the setup isn’t easy, and probably beyond reach for normal users. If you are comfortable with the tech you can offer to set up VPNs for friends and family. Note though that this is a lot of responsibility! You now have access to their browsing if you wanted to spy, and your servers need to be kept safe & up to date.